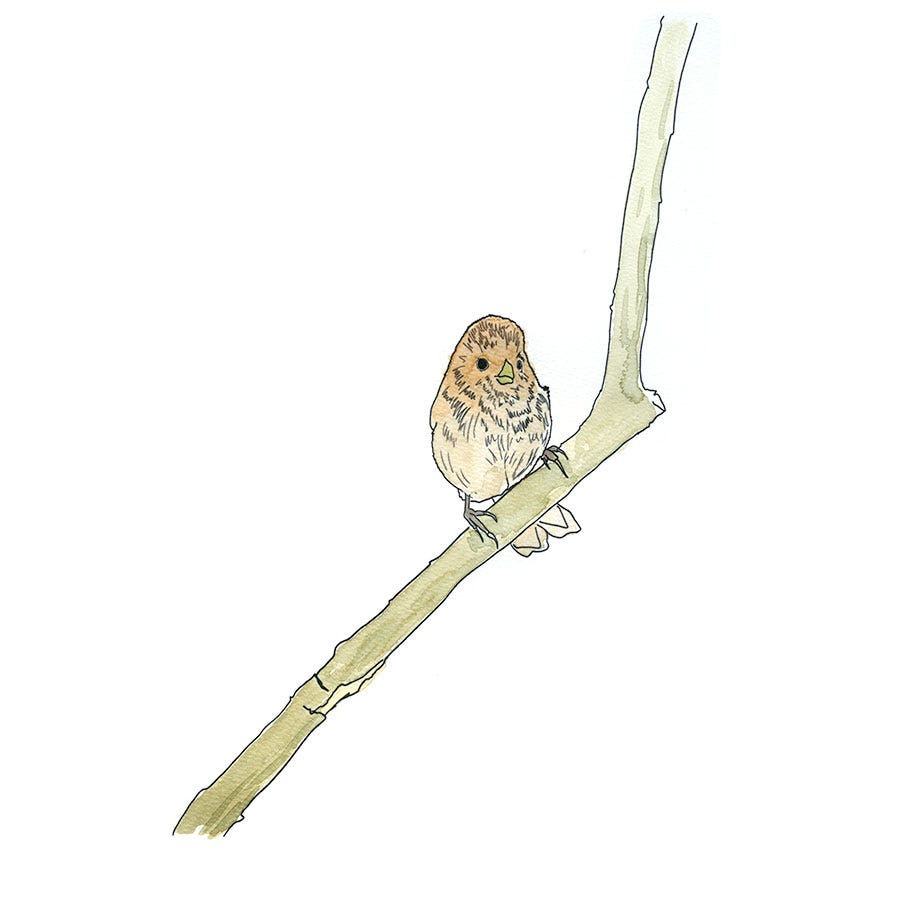

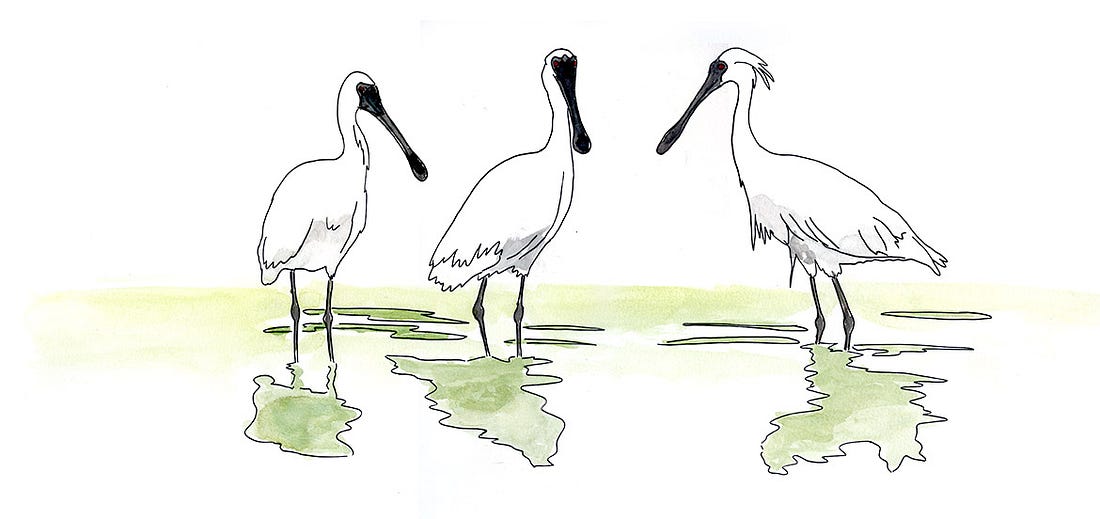

Ganghwa Island: Treaties in the TidelandsGanghwa Island's tidal flats host the endangered Black-faced Spoonbilll, and an overlooked case for cooperation amid rising nationalism and isolationism.You can also read this at Notes from the Road, where the photos and sketches are high-resolution. Nesting each summer on Ganghwa Island, endangered Black-faced Spoonbills find sanctuary in a place shaped by both war and water. At the northwestern fringe of South Korea’s DMZ zone, their survival is a quiet testament to what nations can still achieve together—and a rebuke to the folly of isolationism. I’m traveling to Ganghwa Island with birding guide Byoungwoo Lee, our route tracing the Han River past the Port of Incheon: a sprawl of container vessels, deepwater loading terminals, and vast logistics depots. I wonder aloud how our own trade wars will affect ports like these. But on this bright morning in 2025, I don’t yet know that Incheon is having its best trade year ever. They adapted. It’s my ports—Portland, Tacoma, Oakland, Los Angeles—that are going quiet. Imports are down nearly thirty percent, exports by twenty-five. Ships are sailing half-empty. Dockworkers have lost half their hours. But we’re leaving all that behind. Ganghwa Island is rugged and windswept, lashed to the mainland by bridge and pressed hard against the border of North Korea. It’s a landscape of low granite mountains, rice paddies, ancient Buddhist sanctuaries, and vast tidal flats that stretch toward the Han River estuary. One of the most important stopover points for migratory birds in East Asia. Ganghwa Island’s western shores face the open Yellow Sea, and its eastern shore is largely militarized zones and brackish waters. Ganghwa is part of Incheon, the same one that houses Seoul’s international airport. But unlike Seoul or even mainland Incheon, Ganghwa feels very much apart—it is a patchwork of fishing villages, 7-11 strip malls, fortress ruins, used tire retailers, pensions and quiet woodlands. Ganghwa Island is how I might have imagined Asia as a place distinctly different from the rest of the world. Seoul, for all its energy, feels like other global cities: as sleek, accessible, and cosmopolitan as New York or Paris. But Ganghwa is something else. The houses are tall and narrow, built from unfamiliar materials, tiled roofs and unusual reds and golds and ambers. The streets are quiet, there are no ubiquitous English signs, and you can smell the familiar scent of saltwater flats in the distance. We are crisscrossing the rice paddies of the southeastern section of the island between dikes, looking for geese and raptors. We share these narrow roads with groups of old men fishing. They are fishing for carp, mudfish or snakehead, often with 5 or 6 rods dangling in the water. We stop for lunch in a roadside farming town. It’s a large no-frills buffet with long wooden tables. The buffet is teaming with dishes: kimchi pancakes, seaweed soup, rolled omelets, stir-fried anchovies, cucumber kimchi, soybean sprout soup, bulgogi, braised radish soup, steamed dumplings, scallion pancakes, mini egg-battered meat patties, sesame spinach, sweet potato noodles, zucchini fritters, spicy radish salad, soft tofu stew, rice roll slices, seasoned fernbrake, scallion kimchi, egg-drop soup, spicy mackerel, Pickled napa water kimchi and spicy mudfish stew. Byoungwoo is a skinny and fit guy, but I notice how complete he eats his lunch, and goes back for seconds. At first, he doesn’t even go for napkins. Napkins in Korea are often tiny, just a little bit of paper, and it's not uncommon for Koreans to eat without touching a napkin at all. I think there are a few reasons for this—the whole culture is steeped deep in resource consciousness, not only as a result of post-war poverty, but a modern consciousness about limited resources in a small country—while South Korea is not a true island, its northern border makes it one. The other reason is just how they eat — so neat, so precise, so impeccable. Nevertheless, there is also a reason for Byoungwoo’s full lunch. South Koreans rarely snack—a meal must go a long way. While initially we are the only patrons at the restaurant, as noon arrives, dozens of farmers funnel in. All are men, and all in their fifties, sixties or seventies—the average age of the Korean farmer is 67, and they are aging out fast as younger Koreans flee the country and reject the farming life. When the buffet is filled with what must be 70 or 80 men, all tidily eating with their chopsticks, I recall faintly this scene playing out in a Miyazaki animation. We continue on, driving into a section of foothills and then walking in a mixed farm and woodland habitat — Gray-headed Woodpeckers, Warbling White-eyes and White-cheeked Starlings. A group of about 20 Azure-winged Magpies are chattering as they move between abandoned farmhouses. In the afternoon, as we descend from the low mountains, we can see The Yellow Sea, and miles of shallow flats. These are among the largest in the world, arcing across the shared coasts of China and Korean — endless coast of, estuary, mud and marsh, teeming with life. At low tide, these flats host crabs, burrowing mollusks, and microscopic armies of invertebrates: a buffet for hundreds of thousands of migratory birds who rely on this exact pause in the land-sea equation to refuel on their way from Australia to the Arctic. In South Korea, these flats are called the “getbol”, and we’ve just arrived at the little known Yeocha-ri tidal flats. Hidden in the getbol reeds is a large mammal, staring at us. Byoungwoo refers to him as ‘quite the vampire.’ I don’t quite get this at first, but then I notice his three-inch fangs. Somehow, this Water Deer doesn’t look all that mean—and even with his vicious teeth, actually upper canine tusks used to spar with other male deer — he bounds off in the muddy flats. In 2024, OutKick polled women and discovered that birdwatching ranked as the ninth least desirable trait in men—just behind online trolling, collecting figurines, and taxidermy. Tough crowd. Maybe that’s because all those respondents have never seen what Byoungwoo and I are seeing now—a Vinous Parrotbill—a tiny, floofy orb of feathers that looks like a dumpling grew a beak. If every woman on Earth saw just one, the brunch and spa day industries would collapse, and the women of the world would be out here in the warm afternoon sun, watching Vinous Parrotbills scampering through the heavy brush. We begin to scan beyond the reeds, out at the low-tide pools. Falcated Ducks, Naumann’s Thrushes and Far Eastern Curlews. But then, something captures our attention far off in the distance — a group of large, white birds landing in the salt marsh. I had seen my first Eurasian Spoonbill, the Old World equivalent to the gorgeous coral-colored Roseate Spoonbill of the Americas, many years ago on the Moroccan coast, but — “Wait, these are not Eurasian Spoonbills,” Byoungwoo announces, looking through his scope. “Wait, Black-faced Spoonbills!” These are big, bright white wading birds with a black mask, red eyes and spatula-shaped bill. When they fly closer and begin feeding in the shallows, Byoungwoo immediately understands that we may be among the first people in South Korea to witness their return. They may have come from the coastal wetlands of southern Taiwan or southern China, just having ended their long migration across the Yellow Sea. In the 1980’s, Black-faced Spoonbills were nearly extinct. In 1988, only 288 existed in the wild. At the time, it was among the rarest birds in the world. The reasons were the universal ones we know: habitat loss, pollution, unchecked development along East Asia’s coasts, and perhaps most importantly, a lack of international coordination to protect migratory stopovers. But this bird, strange and comical and ancient-looking, would spark something rare in our time—cooperation between geopolitical adversaries. Unlike many species whose range lies within one nation, the Black-faced Spoonbill’s migration cuts across some of the world’s most politically fraught borders. They breed almost exclusively on small, rocky islets off the west coast of North Korea and in similar habitats in South Korea and northeastern China. Ahead of winter, they disperse along the Yellow Sea and head to southern China, Taiwan, Vietnam’s Red River Delta, Hong Kong, Macau, Jeju Island in South Korea, and parts of southern Japan, including Kyushu and Okinawa. They are now being recorded in Thailand and the Philippines. These are not easy neighbors. Some are technically at war. Others have no formal diplomatic ties. But in the 1990s, conservationists from South Korea, China, Taiwan and Hong Kong began to track the bird’s migrations, and began to see clearly what would be needed to save the species. Then the NGOs got involved. A patchwork of nature reserves began to take shape across Asia’s Pacific Rim. South Korea set aside places like the Namdong Reservoir and a few of the islets off Ganghwa. Taiwan designated the Qigu Wetlands. Even China started protecting parts of its sprawling coastline. And in Hong Kong, researchers began studying the spoonbills where they spend the winter. Despite all the tensions in the region, something rare happened: field biologists, volunteers, and conservationists started working together. They traded notes. They coordinated bird counts. Today, the Black-faced Spoonbill is still endangered, but the population has climbed back to over 6,000. In some places, it’s become a kind of symbol—of what can happen when diplomacy isn’t about politics, but about mud, feathers, and the long game of conservation. And this isn’t just an East Asia thing. In North America, hundreds of migratory species follow invisible routes that stretch from the Canadian north all the way to the mangroves of Central America and the Amazon basin. These birds don’t stop at border crossings. They fly where the food is. Their lives depend on countries working together—countries with different laws, economies, and attitudes about the natural world. Take the Wood Thrush. I sometimes hear its echoing call in the forests of Minnesota. That same bird flies through Mexico and Honduras and spends the winter deep in the jungles of Nicaragua or Costa Rica. Or the Swainson’s Hawk, which migrates from the high plains of the U.S. to the grasslands of Argentina, crossing twenty countries on the way—including places in political chaos. Even the Red Knot, a dumpy little shorebird, depends on a single weeklong feast of horseshoe crab eggs in Delaware Bay before heading on to South America. A missed connection in that chain, as subtle as a single drained wetland, a fence, a bad year for crabs, and the whole system can become unglued. Birds are the real diplomats. They cross war zones and trade zones and disaster zones without knowing the difference. They remind us that ecosystems aren’t local. They’re shared. And the only way to protect them is to act like they are. To care for birds is to care for corridors—those transboundary habitats of shared ecological duty. Sure, Byoungwoo and I care about saving the Black-faced Spoonbill. But if the spoonbills, the Wood Thrushes, or the Swainson’s Hawks vanished, the planet would still be here. These birds are like documents inside manila folders, tucked in cabinets within a vast archive—it's that entire archive that's at risk when autocrats, strongmen, and isolationists pull out of environmental treaties. Today, there are far too many of those bastards—and we need to send them to the dustbin of history. Black-faced Spoonbills show that international cooperation can be cultivated in the most tenuous of political situations, but it also shows what’s at risk when isolationist leaders reject the model that environmental progress must remain borderless. A new wave of autocrats, drunk on nationalism and isolationism, have pulled out of vital environmental treaties, slashed science funding, and dismissed regional and global environmental cooperation. Here in the U.S., Trump withdrew from UNESCO in 2018, calling the United Nations cultural and environmental agency anti-American. Of course, UNESCO plays a key role in preserving global wetlands, World Heritage sites, and biosphere reserves—the exact kind of cooperative networks that make species like the Black-faced Spoonbill or the Monarch Butterfly survive across border migrations. Trump’s administration also gutted the Migratory Bird Treaty Act and removed the U.S. from the Paris Agreement twice, showing countries around the world that the U.S. was not interested in shared environmental goals. In 2025, Trump rolled back key protections for the Pacific Islands Heritage Marine National Monument, stripping status from what had been the world’s second-largest marine sanctuary after Papahānaumokuākea. First created by George W. Bush and expanded by Obama, the monument had safeguarded almost 500,000 square miles of ocean—home to seabirds, coral reefs, and critical fisheries. Though entirely within U.S. waters, its ecological value stretched across the Pacific. Gutting its protections unraveled one of the most significant bipartisan conservation wins in American history. South Korea’s own recently impeached president, Yoon Suk Yeol, copying Trump, followed a similar run of environmental isolationism. Under his leadership, Korea pulled out of a planned international partnership with Japan and China to jointly tackle air pollution and fine dust, despite overwhelming evidence that these pollutants were a common problem that could only be resolved with common solutions. In Argentina, climate-denying President Javier Milei has gone even further, dismantling the country’s environment ministry entirely and gutting protections for protected lands and indigenous territories. His vision of a free market Argentina includes removing environmental oversight altogether—treating biodiversity as an obstacle to economic growth. Brazil’s former Trump-imitating president Jair Bolsonaro turned one of the world’s most vital global carbon sinks—the Amazon—into his personal battleground against global conservation. Rejecting international oversight and dismissing climate concerns as foreign meddling, Bolsonaro slashed funding to environmental enforcement agencies and fired scientists who challenged his policies. He railed against the principles of the Paris Agreement while at the same time ending Brazil’s role in the Amazon Cooperation Treaty Organization. Under his watch, deforestation surged, and Indigenous defenders were silenced or killed—casualties of an isolationist nationalism that viewed global cooperation as a threat. The Philippines leader, Rodrigo Duterte, attacked environmental treaties by systematically destroying domestic protections and sidelining transboundary conservation goals. He called the United Nations ‘useless’, and threatened to withdraw from it entirely, while at the same time stalling on international environmental collaborations of which The Philippines had long been a part. While illegal fishing and coral reef destruction escalated, Duterte expelled or intimidated foreign researchers and NGOs who challenged his regime. To solve climate change, ocean acidification, deforestation, and mass extinction — tasks upon which human civilization rests — we already have most of what we need—scientifically and economically. Renewable energy is cheaper than coal. Agricultural methods to sequester carbon and preserve biodiversity are widely available and know to be successful even among large-scale farmers. Ocean and habitat restoration models are proven and scalable. We have the tools, and global markets are aligning. The free market is ready. The easy part, we now know, is the how. The hard part, the part that is keeping us from the pace of progress we need—is not technological or economic. What’s missing is the political will to remove the roadblocks in order to forge sustaining international environmental agreements strong enough to carry these solutions across borders. In other words, it’s the international treaties that matter the most. And that’s where the forces of nationalism and authoritarianism keep rearing their ugly heads. Every time one of these isolationist leaders say, “Why should we act if China won’t?” they’re not offering a critique. They’re making an excuse and reinforcing the myth that environmental progress depends on perfection, rather than cooperation. Yes, countries like Russia and China have authoritarian regimes. India struggles with balancing development and environmental protection. But when others throw up their hands and say global cooperation is impossible, it is to ignore the millions of citizens in every country—scientists, teachers, farmers, students, thinkers—who believe that a livable planet is central to everything. Who understand that migratory birds don’t carry passports. That climate change doesn’t stop at the DMZ or the Rio Grande. Who understand that peace and biodiversity go hand in hand. Environmental treaties, from the Paris Agreement to regional wetland compacts, aren’t just bureaucratic paperwork—they are civilization’s immune response. They may be imperfect, slow, and often under attack. But they are the only way we scale our solutions fast enough to matter. Pulling out of them—as Trump, Bolsonaro, Milei, and others have done—isn’t strength, but sabotage. And the ultimate folly of isolationism is that it leaves a nation alone in a burning house, arguing about blame instead of grabbing the hose. What happens next won’t be decided in culture wars. It’ll depend on whether we protect what’s shared—or let it fall apart. The spoonbill doesn’t know it’s crossing borders. It just follows the same path it always has. The real question is whether we’ll reject isolationism, embrace transboundary cooperation, and help the planet begin to heal. Notes from the Road is free today. But if you enjoyed this post, you can tell Notes from the Road that their writing is valuable by pledging a future subscription. You won't be charged unless they enable payments. |